AVAC: Where the Pipe Curves

Observations from the part of the meeting most people stop listening to. Notes about maintenance, responsibility, and who was in the room.

This is the final installment in my notes from the December 2nd, Operations Advisory Committee meeting, following “An Emergency, Apparently” and “Rust Is Funny Until It Isn’t”.

The room was small, almost apologetic in its proportions. A square of tables pressed together, a screen pressed forward, everyone pressed inward. When Mary C. Cunneen, Acting Chief Operating Officer of the Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation, began speaking about the AVAC system, there was very little physical space left for the thing she was trying to explain.

She raised her hands anyway. And I found myself unexpectedly excited, unaccustomed to seeing Mary so vivid, so physical, so entirely at ease inhabiting the explanation rather than guarding it.

Mary reminded the committee that the year before, RIOC had paid to replace a section of pipe at the entrance to the AVAC plant itself. This proposal, she said, concerned a different section. The West Main line, under Main Street, just outside the plant. She explained that certain parts of the system are more vulnerable than others, especially curves, where garbage repeatedly slams into the pipe over decades.

A brief note:

This newsletter is written once a week and supported almost entirely by readers sharing it quietly with one another. If you were forwarded this, subscribing ensures it arrives without relying on someone else to remember you.

She demonstrated this by slapping her hands together in quick, rhythmic motions. It was the most animated garbage disposal explanation I have ever witnessed, and unfortunately, almost no one could see it. The slide deck filled most of the visual field, and the gesture existed largely in sound.

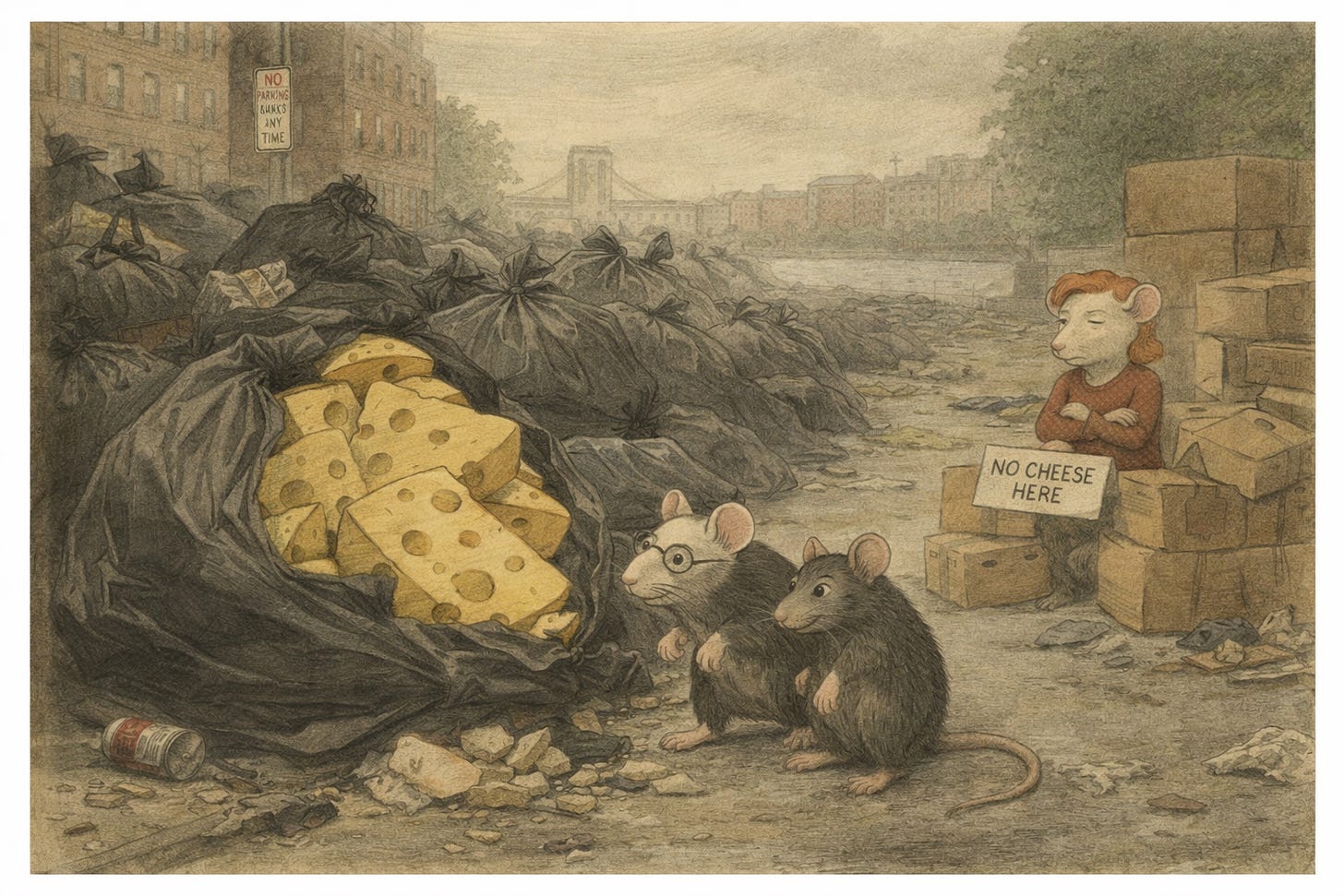

The logic itself was straightforward. Curves take more impact. Impact causes wear. Wear eventually becomes failure. The work, she said, needed to happen now. Garbage slamming into pipes for decades is the most accurate metaphor for governance I’ve heard this year.

Mary explained that Envac, the original installer of the AVAC system, would perform the work. She emphasized, carefully and more than once, that this was a single-source vendor. Envac installed the system in the 1970s. Envac maintains it. Envac is the only entity qualified to do this work.

“Given the single source nature of this project,” she said, setting up the number.

Three hundred sixty thousand dollars.

She said it again, this time rounding up just shy of three hundred sixty-one thousand. Even she seemed to feel the weight of it as it landed in the room. It is a lot of money for a pipe. Even if you know nothing about pipes, as I do. Infrastructure often costs more than intuition would allow. Three hundred sixty thousand dollars for a pipe sounds outrageous until you remember it’s underground and therefore immune to common sense.

I found myself suspended between two familiar instincts. One is to trust expertise. The other is to recognize how monopoly language works when it appears fully formed, already justified, already complete. I thought of stories I have read over the years about public agencies that tried to save money by cutting corners, only to discover later that when trains run over tracks, or when systems carry weight at speed, the material matters. The structure matters. Everything matters.

And still, the idea that only one company can replace a piece of a decades old design gives me pause. It sounds odd. It may also be true.

Mary moved on.

In the Middle of It

I have not always been kind to Mary Cunneen in my notes over the years. In earlier meetings, she often sounded guarded, brittle, sometimes condescending. This time, she did not. Her voice was calmer. Softer. There was confidence there, but not the defensive kind. She seemed steadier in herself.

Confidence without defensiveness is terrifying. It means the armor came off because it’s no longer needed.

I have learned, late in life, to pay attention when someone changes how they occupy a room. Mary appears to be doing that. I admire any woman who makes her way into the upper ranks of a system like this one. Men love to call women tyrants. It saves them the trouble of learning how to follow instructions. Men like to confuse structure with cruelty when they are asked to follow it. Funny how structure always feels cruel to people who benefit from chaos.

She is growing in the role. I can see it. And I respect it. You can tell she’s growing into the role because she’s stopped apologizing for occupying space that was never meant to be comfortable.

A Shift in the Conversation

Then Melissa Wade, a member of the committee, asked a question that had almost nothing to do with the pipe being replaced. She didn’t ask about cost, vendors, or timelines. That’s how you know the question was dangerous.

She asked about origin.

We often hear, she said, that residents put the wrong materials into the chutes, contributing to the deterioration of the AVAC system. Would it make sense, she wondered, to look at the size of the chutes themselves. What she implied was that everyone blames residents for misuse, which is amazing considering the system was designed assuming perfect behavior. If buildings have large openings, does that make it easier for large items to be discarded improperly. Would it be worth considering requiring smaller chutes, so misuse is less possible in the first place. Smaller chutes to prevent misuse? That’s called design. It’s very controversial.

It was the most intelligent question I have heard in a committee meeting in years because it suggested fixing the cause instead of funding the consequence.

Mary immediately complimented her. A genuine one.

Alvaro Santamaria, Assistant Vice President of Engineering and Capital Projects, responded next, clearly eager to speak, as men often are when a technical word opens the door. He spoke about pipe diameters and transitions, about how internal piping must match the diameter of the main lines, how funneling can cause problems. None of it was wrong. None of it was unkind. It simply was not what Melissa had asked. Everything he said was correct, detailed, and completely unrelated. He had seized on a word she used and let it pull him away from the essence of her question, not out of malice, but out of habit.

She clarified gently, which women learn to do early. She wasn’t asking about the pipes. She was asking about the hole. The opening where she, personally, drops her bag of garbage. The size of that opening determines the size of what can go into the system.

Alvaro acknowledged the point and added that buildings are often reluctant to invest in modifying their chutes. That is amazing, considering how expensive it gets when they don’t.

Yet, there it was, again.

RIOC blames residents.

Residents can only use what buildings give them.

Buildings do not want to spend the money.

For years, I have found myself caught between two explanations that never quite added up. On one side, David Stone’s writing, which at times made RIOC sound omnipotent, controlling every failure by design. On the other, RIOC’s refrain about mattresses and misuse, which sounded increasingly implausible as a comprehensive explanation. Mattresses became the villain because blaming objects is easier than blaming decisions.

And here, for the first time, someone was pointing to the architecture of responsibility itself. Once you see the architecture of responsibility, the excuses stop fitting through the opening.

Before the Meeting Moved On

Melissa continued, gently, suggesting that if buildings are unable or unwilling to properly educate tenants on AVAC use, perhaps reducing chute size should be part of the conversation. Not to punish residents, but to protect the system.

Mary said perhaps it was something that could be discussed.

Then Howard Polivy jumped in, referencing a discussion with Brian Weisberg from Manhattan Park. Howard jumped in to reference a conversation, because nothing settles a question like mentioning you once talked to someone. Before he could finish the sentence, Fay Christian spoke over him, eager to add that Manhattan Park had already had a large discussion about this issue and that Brian was looking into it.

As best I could tell, the idea that emerged from this overlapping exchange was to lock the chutes during move-outs. At least, that seemed to be the point, though no one quite said it cleanly. It was presented as something already discussed, already considered, already underway.

Neither completed a full thought. They stepped on each other, politely but unmistakably. The eagerness to demonstrate involvement was palpable. It mattered less what the solution was than that it had already been talked about. And as I listened, I found myself wondering what meeting this had been, and who had been in the room for it. Howard and Fay were clearly eager to establish that they had been there.

Nothing stalls progress faster than two people racing to prove they were already thinking about it. I found myself wondering when that discussion took place. And why some committee members were in the room for it, while others were not. These are the kinds of questions you do not ask out loud, but you should.

Melissa, instinctively fair, responded that she was not a fan of penalizing neighbors who are not moving out. Punishing people for staying is a fascinating housing policy, even by Island standards.

The committee then struggled briefly with language around recommending a course of action that had, functionally, already been included in the agenda. They found the words eventually. Or something close enough.

The meeting moved on.

The remainder focused on winter preparedness. Lydia Tang raised concerns about flooding near Westview following the removal of the glass atrium. She and Melissa helped clarify that certain promenade maintenance on the Queens side falls squarely under RIOC’s responsibility. Alvaro outlined recent renovations and plans with a level of detail that felt real. Competent. Grounded.

For a moment, it felt like actual work. No theater, no props, no applause. Very unsettling.

As the meeting wound down, I found myself returning to the suggestion that had slipped out almost accidentally: locking the chutes during move-outs. That, at least, seemed to be the idea. Not debated. Not voted on. Simply referenced as something already discussed somewhere else.

It lingered with me because it explained more than it solved. The solution itself was less interesting than the way it arrived, carried in sideways through overlapping sentences and unfinished thoughts. It mattered that Howard and Fay were eager to signal they had been part of that earlier conversation. Presence was being established, which is the polite way of saying territory was being marked.

And so the question that stayed with me was not whether locking chutes during move-outs is a good idea. It was where that decision-making had taken place, and who had been invited into it. Because maintenance does not fail all at once. It fails when decisions migrate quietly away from the rooms meant to hold them. When decisions migrate quietly, accountability never follows.

As attention shifted elsewhere, I found myself thinking about maintenance again. About how it only becomes visible when something breaks. About how unglamorous it is. About how essential.

We build. We celebrate. We cut ribbons.

And then, quietly, year after year, someone has to show up and make sure the systems still hold. That work does not photograph well. It does not trend. But it is the only thing that keeps a place livable.

When the meeting ended, the room did not change. It simply emptied. The questions lingered longer than the answers. And for once, that felt appropriate.

We do not need viral. We need thoughtful forwards to people who care. If you are one of them, thank you.

I’ve lived in Island House for 37 years first on the 15th floor and now on the 7th. The AVAC rooms, that are not handicap accessible, have a very small chute opening. When you open the chute door there is no big open space into the chute but a metal piece that is part of the door to the chute that sticks up not allowing big items to fit down into it. Many years ago I learned that the smaller the garbage bag the easier it was to put any garbage into that small space allowance without having to squeeze it in. Island House residents are told that if they have big items that need disposal to just call maintenance and they will pick it up from inside the AVAC room. I could never figure out how someone could have been able to put a bed frame down a chute unless other buildings have large chute openings in the wall with nothing blocking their ability to throw whatever they have into it. Seems like a no brainer but there are a lot of quirky design flaws in these buildings.

Fond reminiscence of past incomplete solutions, sucks the air out of honest progress and murders a good outcome for the problem.