An Emergency, Apparently

A demolition rushed, an explanation missing, and a community left outside the room.

The snow had just started drifting past my window when I finally sat down to watch the Operations Advisory Committee meeting from December 2, 2025, a session meant to brief the public on the fate of the old steam plant and the so-called emergency behind its sudden demolition timeline when Fay Christian began the meeting by reading names as though she were auditioning for the role of “news anchor who forgot she’s also in the script.” Titles slipped, pronunciations staggered, and respect wandered in and out depending on who sat where.

Before anything was said about public safety or demolition schedules, Fay Christian breezed past Professor Tang’s credentials as if the word professor might burn her tongue. The contrast sharpened when Mary Cuneen’s name appeared; Fay lingered on “VP” with a kind of practiced warmth, a small elevation that felt almost ceremonial.

Then there was Dhruvika. After a year of introductions, Fay still handled her name the way I once handled my first electric typewriter in the early sixties, with optimism, confusion, and a faint hope no one was watching. But it was the smile that gave the moment away. Not embarrassment, not friendliness, but something far more curated. The kind of smile that travels upward without ever touching the heart. A smile meant to signal who stands above and who stands below.

Only later did I understand why this felt so familiar. Fay’s interactions took me back to my volunteer days on Welfare Island in the early sixties, when a nurse at Goldwater Hospital would whisper certain names with care and let others fall away entirely, depending on who mattered and who didn’t. Some things change. Some things simply trade uniforms.

Words That Sound Like Warnings

When Rachel Swack of HPD took the microphone, the word “emergency” appeared so often it might as well have been punctuation. Every other sentence landed on it, softly and politely, the way some people say “dah” without realizing it has become a kind of verbal wallpaper. Rachel was unfailingly pleasant throughout the night, repeating what others said, making them feel heard, even jotting notes in a small pad. Watching her write, I could almost read the line forming in her mind: “When will this person stop talking?” She hid it well. Too well. If I were anyone else, I might have been fooled.

She spoke as someone trained to absorb a room, to neutralize it with kindness. Yet when asked what the actual emergency was, she could not quite say. No one from her team was there to assist her either, which made her warmth feel both genuine and strangely hollow.

The steam plant has been closed since 2013, but apparently the emergency only began once the question of who pays was settled. It reminded me of other island rhythms of late, where urgency blooms only after the ink is dry somewhere else. Much like the new ten year lease extension that seemed to find its way to the board only the night before the governor’s announcement, long after the real decisions had been made.

If you send information to an advisory committee after the project has already begun, it isn’t consultation. It’s breadcrumbing. A trail left behind so the public can be told, later, that they were advised.

Judy and the Architect

Bless Judy Burdy. She said what every resident was thinking within the first ten minutes, and she said it with the same unstoppable velocity she brings to every room she enters. I adore her, truly, even if she is a fast‑track train with one conductor and that conductor is always Judy. She asked the questions no one else on the committee dared to utter. Why the rush? Why now? Why call something an emergency only after twelve quiet years and a conveniently timed funding agreement? She spoke about Goldwater Hospital’s demolition, how long it took, how careful it was, how nothing about this current pace made sense. She reminded the room of the subway line, the bridge, the steam tunnel underfoot. Judy does not nibble at a point. She bites.

Then came the architect, and the room shifted. She was calm, sharp, deliberate. Her words didn’t flare; they landed. She separated structure from story the way only a trained eye can. No theatrics, no raised voice, just a clear professional assessment that the building showed no visible signs of an emergency. She held the HPD report in her hand without even needing to open it and said what half the room already suspected: forensic work this was not. And when she said that emergencies declared without evidence often look a lot like opportunities, I felt the entire meeting inhale.

Rachel tried to keep her footing, but the architect kept returning to the same immovable question: What exactly is the emergency? And each time Rachel circled back with softness and repetition, the answer dissolved. She didn’t know. She admitted she wasn’t the engineer. She promised to “look into documentation.” Her words were polite, practiced, hollow.

It was Fay who stepped in to rescue her, offering a muddled, well‑intentioned sentence that revealed she did not know much either. Two people answering a question without an answer, trying to steady a narrative that had already begun to unravel. What they had not anticipated was sitting across from an architect who understood both structure and pretense, and who refused to let the word emergency pass without substance.

Pressed again, Rachel finally admitted she did not know the nature of the emergency and could not elaborate. No engineer from HPD was present. No one at RIOC stepped in to help her either, aside from Fay repeating soft reassurances that only deepened the haze. The silence around her spoke more clearly than any of her notes ever could.

Outside the polite script of the meeting, the explanation travels in quieter hallways: the emergency is less about imminent danger and more about timing. A land‑lease extension negotiated behind closed doors, a development window opening, and a parcel that has sat untouched for over a decade now needing to be cleared with sudden urgency. A coincidence so convenient it no longer bothers to disguise itself.

The Process That Already Happened Without Us

It was Melissa Wade who slipped the truth into the room as calmly as a librarian sliding a note across the desk. She began not with accusations or theatrics but with simple, precise questions about the project timeline Rachel was supposedly representing. And with each answer Rachel offered, three truths revealed themselves.

First, the project was already in week three. The community had been invited in long after agreements were signed and work was underway. This meeting was not the start of anything. It was the documentation of something already rolling downhill.

Second, Rachel had no idea what was being done on the site. Each of Melissa’s gentle questions returned the same soft refrain: “I believe that is true.” Not confirmation. Not clarity. Just the verbal equivalent of nodding at a stranger’s grocery list.

And third, Melissa revealed that the next six weeks were not demolition at all but setup and configuration. A slow-building hint for anyone paying attention: if the public hoped to challenge the process, or even understand how to request a pause, their window was now.

Melissa’s questions dovetailed with the groundwork Judy and the architect had already laid, and together the three of them revealed what no one at the table meant to show. They punctured the performance. They exposed that the person presenting the emergency could not describe it, and that the structure of the process had been designed to outrun public involvement entirely. And Melissa connected the final dots: the project was already underway, and if there is any path to slowing or questioning it, the clock is already ticking.

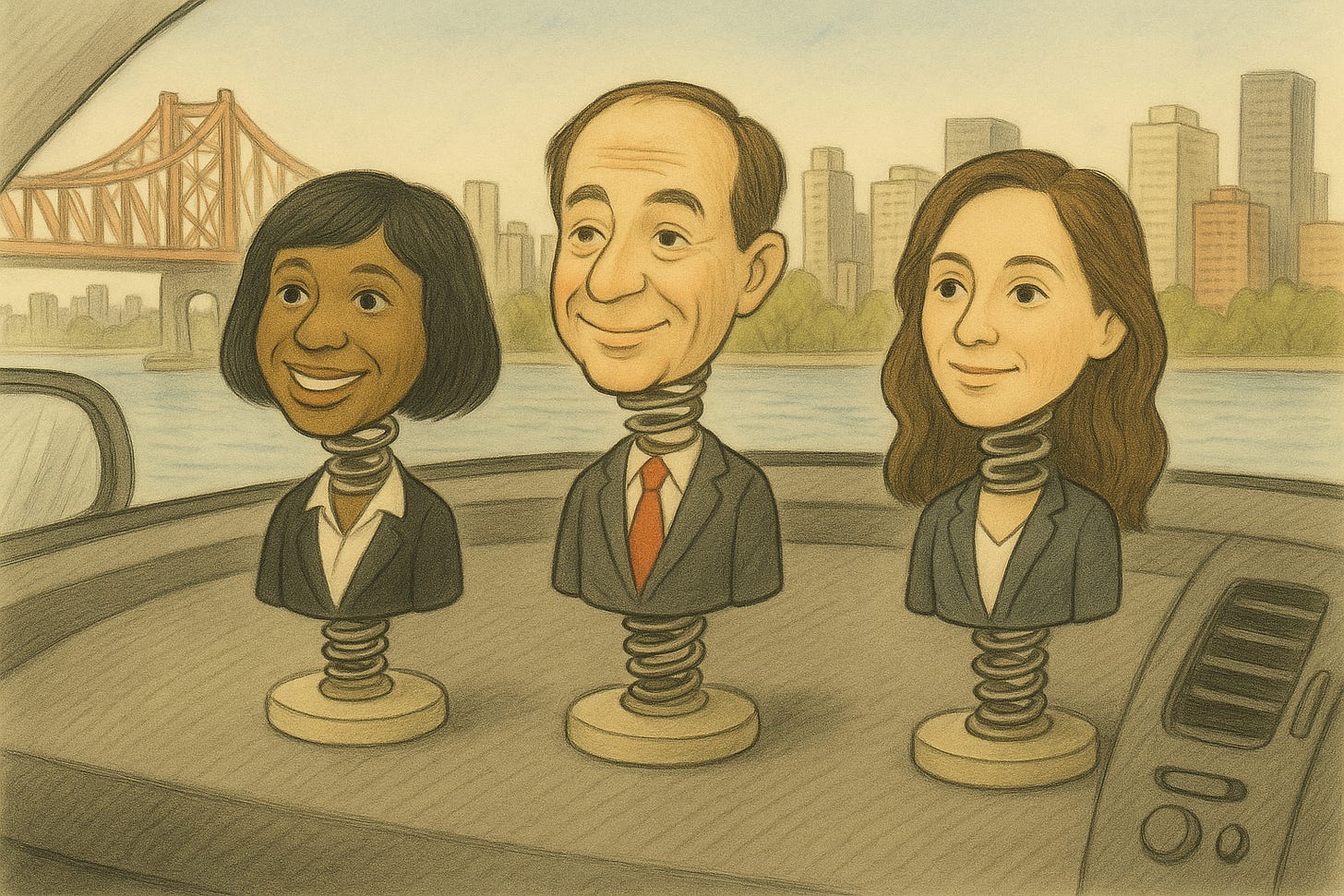

The Bobbleheads

When Lydia Tang asked whether this would go before the board for a vote, the synchronized head shakes of no from Fay, Howard, Mary, BJ, and Rachel looked like a row of bobbleheads in a gift shop. Even Dhru, sweet soul, glanced at BJ first before deciding which way to tilt.

But what struck me more were the still ones. Melissa, Lydia herself, and Lada Stasko did not move a muscle. They watched, quietly and without a flicker of assent, as though they were seeing a script they had not been asked to rehearse. It made me wonder who had been in the pre‑meeting and who hadn’t. Some people seemed to know their cues. Others were absorbing the play in real time.

Fay and Howard felt coordinated, a practiced pair. Mary and BJ moved in the same rhythm as well. And Dhru hesitated, caught between following the pattern or following her instinct. The choreography told its own story: decisions had already settled somewhere else, and the motion in the room was merely the echo.

Of course there would be no vote. When something is labeled an emergency, process becomes optional.

Meanwhile, the real emergency the steam tunnels beneath our feet received the kind of polite, passing interest usually reserved for a distant cousin’s recent gallbladder surgery.

And that, perhaps, is the only honest moment of the night.

Because on this island, danger isn’t what decides urgency. Development does.

I watched the snowfall outside as the topic wound down, remembering the old ferry rides in the sixties when buildings here existed to shelter, not to profit. I thought of the patients I read to in the old hospital, how the steam plant once hummed warm in the dead of winter.

Now it sits cold, and somehow that is when it became urgent.

Sometimes the building isn’t the thing collapsing. Sometimes it’s the public process meant to protect us.

Makes you want to weep. Yes, weep.

Eleanor, thank you. Your observations are the real record residents have been craving for years. You are doing something no one else could have or ever did. The moment Melissa revealed that the project was already in week three, it blew my mind and enraged me. You cannot have an emergency that starts after the contractor clocks in.