Fast Track At Home

What Roosevelt Island Teaches About the Ballot’s “Speed” Proposal

The citywide election is weeks away. Buried under the personality talk is a proposal that promises speed: fast track approvals for “affordable housing.” Before Roosevelt Island voters decide what that should mean for New York, it’s worth asking what it already means here. Our island has been living inside a version of fast track for years.

Roosevelt Island is already on a fast track

Most neighborhoods move through public boards, local hearings, and a Council vote that can take months. Roosevelt Island, by structure, does not. The decisive instruments are state ground leases, regulatory agreements, and financing papers. The RIOC board is the visible stoplight, but too often it functions as the last green light. The public learns the terms after the ink has dried.

The ballot pitch assumes locals are the bottleneck and contractors are straining to deliver true affordability and quality of life. Our island shows a different reality. Behind closed doors, sponsors push state and city partners to relax guardrails, widen profit channels, and rebrand narrow workforce allocations as affordability. Then come the institutional carve outs. A large nonprofit becomes the landlord, pays no taxes, and shifts the long-term load back onto RIOC’s operations. New square footage without local revenue means thinner budgets for streets, parks, and basic services.

This has been visible to anyone who listened. David Stone has warned that RIOC can look sustainable on paper while the longer horizon says otherwise. RIOC CFO Dhruvika Patel Amin has flagged the same pressure in public meetings. Keep adding projects that reduce real revenue and concentrate management burdens and the math stops penciling out. That is not a theory about community input. It is arithmetic produced by a process that prizes speed and private profit first.

Where Process Becomes Power

Fast track is marketed as a timing reform. In practice it redistributes leverage. Compress the steps where a community kicks the tires and you reward whoever already sits in the decision room. On this island that is not residents. It is a small circle of state decision makers and a smaller circle of very powerful developers and institutions.

REDAC: The Quiet Committee

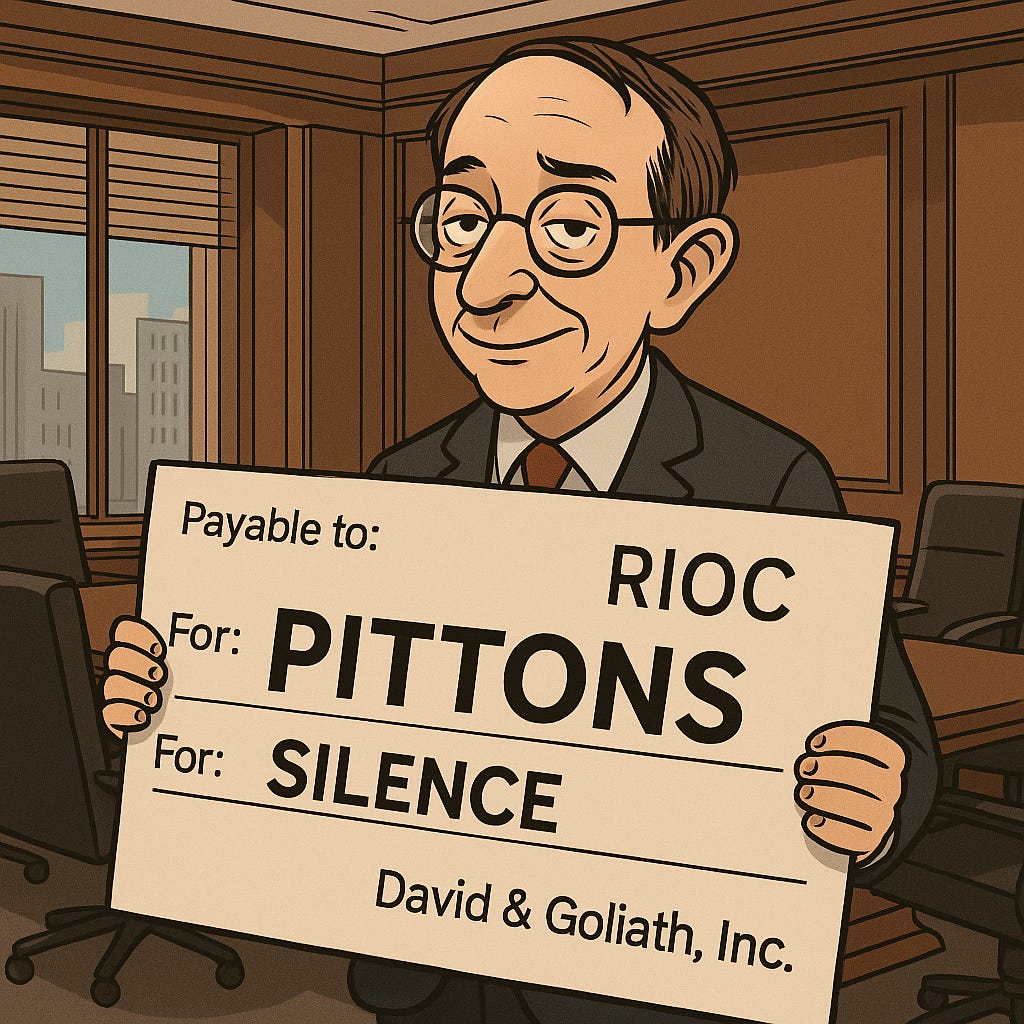

Howard Polivy chairs RIOC’s Real Estate Development Advisory Committee, where property deals are supposed to be tested before board votes. On Roosevelt Island the chair does more than run meetings. He sets the tempo and defines what counts as normal.

The record shows REDAC rarely meets. When it does, items arrive as briefings, not decisions, and the public learns about them after the outcome is set. The contrast with Professor Tang’s Governance Committee is stark. She convened real working sessions that shaped bylaws, ethics rules, and operating standards. REDAC, by comparison, has offered a handful of thin meetings.

In theory, REDAC is the island’s local guardrail — a place to pressure-test public deals before they reach the boardroom. In practice, it rarely meets. When it does, the topics are stripped of substance, framed as briefings rather than decisions. By the time the public catches up to the issue, it’s already over. Under Polivy’s leadership, the committee operates at the bare minimum, carefully avoiding the kind of debate that would illuminate how real estate power actually moves through RIOC.

Polivy also chairs Audit and Budget — two levers that, together, control flow and oversight. Each year, during the ceremonies of the Audit Committee, he delivers the same soft assurance: a few polished words about prudence and procedure. If you spliced together clips from the past five years, you wouldn’t know what year you were hearing. It all blends — the same phrasing, the same calm tone, the same absence of scrutiny. Multiple internal sources describe him as the board Chair Visnauskas’s reliable closer. The state sets direction, Polivy smooths it through, and REDAC serves as the final rubber stamp between Albany’s quiet asks and the developers who profit.

The connection to Southtown and the Related playbook

Southtown was sold as a neighborhood delivered in nine buildings, with affordability that would honor the island’s founding promise. Look closely and you see how speed plus access reshapes that promise.

Instead of distributing affordable homes across addresses so that each building owned a share of community, large blocks were carved out for institutions and one-off solutions. Memorial Sloan Kettering received an entire building for its workforce. The units are not open to the public, the owner is tax exempt, and the impact on RIOC’s finances is far from neutral. Call it housing, but it is not the kind that increases open-market affordability for island residents — nor one that helps sustain the HVAC, sanitation, or infrastructure systems RIOC maintains for everyone else. It adds strain to the buildings that do pay, forcing those residents and owners to carry a larger share of the island’s operating costs.

Building 8: the compliance tower

By all accounts, Building 8 became the single-point solution to affordability obligations. It grew beyond early expectations, justified at the time as a gift to the island — one large, fully affordable building that would check every box at once. The gift came with a catch. Consolidation is tidy for a developer because it allows a single entity to live off state and city rent flows while insulating the rest of the portfolio from obligation. It’s tidy for a spreadsheet, not for a neighborhood.

On the ground, concentrating affordability in one tower has social costs that never appeared in the slide deck. Tenants and neighbors describe the quiet frictions that come from containment. Public Safety became the daily stabilizer. None of this indicts the residents. It indicts the policy — a model that trades integration for compliance. You can call it housing policy. You can call it a win on paper. It is not community.

As we dig deeper into RIOC’s own records a picture emerges. Page by page, the veil lifts on terms that have never seen daylight. The documents show how public oversight gave way to private negotiation, and how transparency was redefined as a courtesy. Had there been real public debate, with city-level guardrails, hearings, and local accountability, would Southtown’s “affordable” solution have looked any different? Or was the isolation of Building 8 always the plan?

What Speed Without Daylight Produces

Speed is not the enemy, but speed without daylight picks winners. On Roosevelt Island, those winners are the ones with direct lines to state decision makers. The rest — the households excluded from institutional housing, the residents absorbing the management strain that concentration creates, the taxpayers watching tax-exempt allocations strip long-term revenue from the authority that keeps their streets, parks, and public safety afloat — are left paying more for less.

Southtown was calibrated for yield. Mixed income existed, but only in ways that protected profit. The most lucrative buildings stayed clean of obligation, while “affordability” was pushed into corners — concentrated, contained, and isolated from the market towers that define the skyline. Over time, the plan shifted from promise to sequence: a string of quiet revisions, at least six major scope changes by our count. Each might look harmless on its own, but together they tell a single story about leverage. When the rules bend and the timeline compresses, the party with the lawyers and the lobbyists writes the edits. Residents get the summary — never the pages underneath.

The Sign That Chooses Sides

It’s just after 1 p.m. on a Saturday, and the tram platform breathes like a crowded lung. Strollers wedge against backpacks. A toddler waves a pretzel stick as if blessing the line. Residents time their breaths between the sweet fog of someone else’s vape. The queue spills down the stairs and unfurls across the plaza—orderly, resigned. Tourists carry ur…

The Underlying Pages

The next chapter is already being outlined.

For a year, rumors have moved quietly across the island about more buildings. Those rumors are no longer just rumors. Sources in the state, the city, and within RIOC confirm that new construction is being discussed, possibly three buildings, outside what residents long understood to be the original Southtown lease vision. The locations are not public. The timing is not public. The public, as usual, is expected to react after the negotiations are finished and the ink is dry.

Despite years of rumors about new buildings and lease extensions, REDAC has never publicly discussed them. The silence is not oversight; it is design. Howard’s committee does not challenge direction — it follows it. The only open question is whose: the state’s, the contractors’, or both. When the Inspector General’s report hinted that deeper reforms were needed within RIOC but stopped short of naming names, some on the island read that silence as its own signal.

As David Stone astutely observed historically, there is a growing probability that we will soon be graced with an on-island appearance by RIOC’s official chair, RuthAnne Visnauskas, to frame a new lease extension alongside a few “bonus buildings” negotiated beyond public reach. When that day comes, the record will show that the topic was “discussed” in REDAC and “approved” by the full board — neat, procedural, and complete. But where, exactly, is the local power in that process? Who decides what buildings we need, where they belong, and how they reshape the tax burden that drives every rent, maintenance fee, and operational cost on this island?

Closing Argument

When Buildings 8 and 9 reached the RIOC board, the paperwork arrived only days before the vote. Members were told that a funding window tied to affordable-housing programs would close within days if they delayed. The board approved the package with minimal debate. Later filings suggest the urgency was overstated, the financing advanced on a slower schedule than the one used to justify the rush.

Fay Christian voiced a mild objection but stopped short of dissent. The rest of the entrenched leadership, Howard Polivy, Margie Smith, and David Krout among them, signaled support, echoing the tone set by the developers’ representatives. Over the years, each has been publicly associated with positions broadly sympathetic to the contractors’ interests, both in and outside board settings.

Among the promised community benefits were upgrades to Firefighter Field, restrooms, lighting, and after-hours access. Those improvements never materialized. No record in RIOC’s budgets or project updates shows that the commitments were enforced. The pattern is familiar: a deadline set by developers, a board pressed to comply, and oversight dissolved in the rush to stamp “yes.”

We have seen this play before: a few hands hold the pen while the rest of the island waits for the reveal. Speed is sold as efficiency but functions as control, with the same choreography every time: the meeting after the deal, the hearing after the vote, the applause for transparency after the curtains close. If the city wants fast track, radical disclosure and binding guardrails must be the price of admission, or the model that produced a compliance tower and institutional carveouts here will simply scale citywide. We are still prying open the Southtown ground leases and will publish what we can obtain, including a timeline of how Building 8 grew, who called that growth a gift, and how it reshaped the ground beneath it. The board dynamic is beginning to shift as newer members ask unscripted questions and push local priorities, but until REDAC becomes a forum for negotiation rather than confirmation, Roosevelt Island will keep learning about its future only after the ink dries.

I clicked yes for affordability, then realized it meant another tower. Clicked no and felt like I’d evicted myself. Democracy by guilt trip, love that for us.